Forest Awakened

Illustrating Trees in Mediterranean Art

ASBA Botanical Artist, December, 2023

by Carol Jean Rogalski

Carol Jean Rogalski

is a retired clinical psychologist who worked with military veterans and substance abusers for 40 years. During her research on opium usage, she discovered The Morton Arboretum’s botanical art program, which has since become one of her interests.

It has been my desire, for a considerable amount of time, to document the art of the tree in Western botanical art and illustration. Since my first reading of Theophrastus of Eresos (371-287 BCE), I was impressed by the beauty and clarity of the writing, but I was reading, of course, a translation, since the original work would have been in Greek. My document on trees has been long in coming, and it may not be due only to my procrastination, but to the complexity of locating materials. I had not been conscious that, since the time of Theophrastus, information was thought to have been passed along only verbally, or in written form without illustration. That may be partially true, yet I am skeptical, since papyrus—upon which writing or illustration took place—was fragile. Scholars state that Theophrastus wrote 300 books on multiple topics, yet only three on plants survive. Theophrastus (philosopher, botanist, physicist) is named along with greats such as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. He has been called the Father of Botany for the systemization of the botanical world. In his two works, Enquiry Into Plants (two volumes) and On the Causes of Plants, he categorized plants into four types. His works were major sources of botanical knowledge during antiquity and the Middle Ages. More than a century after Theophastus, Dionysius Crateus (111-64 BCE), whose herbal was the oldest treatise on pharmacology, is reported to have illustrated the volume. He has been called the Father of Botanical Illustration. Yet despite his work and this exemplary title, we do not look to him for the foundation of pharmaceutical knowledge during the Middle Ages, since neither his writing nor his illustrations survive. I have been unable to locate the two extant images that reportedly exist. One image considered to be a copy of his original survives and is presented here, but it is NOT of a tree.

We look to Pedanius Dioscorides (40-90 CE) (army physician, pharmacologist, botanist) for the surviving encyclopedic text of botanical and medicinal substances in De Materia Medica. According to scholar John M Riddle (1985), Dioscorides may have worked in ink wash on papyrus, and did illustrate his work. This was “assumed since often he did not describe the plant but only its medicinal uses. An accompanying illustration often would have been required…” Ink wash seemed likely, since watercolor would have flaked off a papyrus roll. If there had been illustrations, none have survived. It is about five centuries later, in 512 CE, that Dioscorides’s De Materia Medica was appropriated into a luxury manuscript known as the Juliana Anicia Codex, also called the Vienna Dioscorides or Codex Vindobonensis.

Egyptian fresco

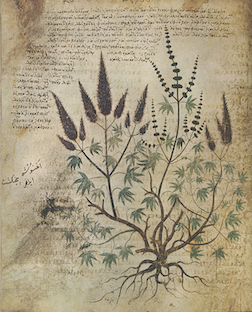

One could now search for plants among 600 specimens, 435 illustrated with 383 extant originals. But I was unable to view this document in Vienna, and would have had to be conversant in Greek, Persian, or Egyptian to understand the notations. Two other significant works based on Dioscorides’s non-illustrated text, and sometimes copied illustrations from the Juliana Anicia Codex, were Codex Neapolitanus (late 6th or early 7th century) and Morgan 652 (927-985 CE).

In 1933, Gunther edited a 17th century English translation by Goodyear of the Dioscorides De Materia Medica which included black and white, pen and ink illustrations, copied by Miss F. A. Boustead. While I counted 87 trees or shrubs—included because of their medicinal value—there were only six illustrations. In 2014, a database for three Dioscoridean illustrated herbals incorporated the above three manuscripts. It was developed and made public by the American Society for Horticultural Science. This database is an ongoing work in progress, permitting an open, simple search for images common or unique among the three herbals. The search is simple because data is searchable by herbal, common name in English and Greek, and binomial and botanical family.

My years-long search for the earliest botanical illustrations of trees revealed colorful illustrations of the black and white illustrations originally viewed in the Goodyear/Gunther/Boustead edition: Buckthorn, chaste tree, common juniper, cypress, savin, willow.

Buckthorn, Rhamnus cathartica L., Juliana Anicia Codex

Phoenician juniper, Juniperus phoenicea L., 13th - 14th century, Codex Aniciae Julianae

Lamb’s tongue, Plantago lanceolata, Codex Vindobonensis

Chaste Tree, Vitex agnus-castus L., Juliana Anicia Codex

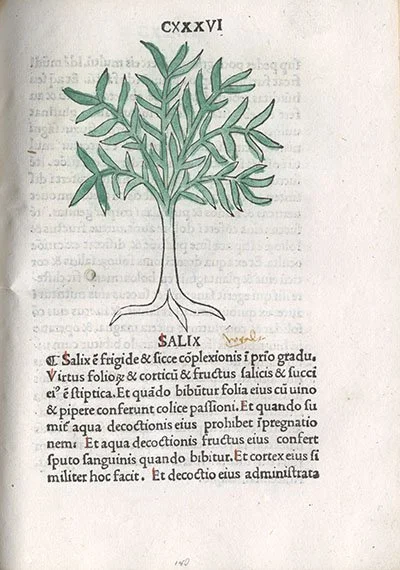

While De Materia Medica has been the foundation of Western pharmaceutical knowledge since the Middle Ages, multiple hybrid manuscripts incorporated botanical texts of Pliny and Pseudo-Apuleius. Four manuscripts were available to me at the Sterling Morton Library of the Morton Arboretum in facsimiles of other important works: Herbal of Pseudo-Apuleius (annotated by F.W.T. Hunger 1935) which contained black and white photographic reproductions of Codex Casinensis 97 copied possibly from 4th and 9th century manuscripts originally at Monte Cassino, with colored illustrations; Editio princeps Romae the first printed edition of colored woodcuts in 1481; Herbal of Apuleius Barbarus /MS Bodley 130 colored illustrations also copied in 11th century in England from Codex Casinensis 97; and Herbarium Latinus most popular colored woodcuts by Peter Schoeffer in Mainz in 1509.

Savin was illustrated in all four manuscripts. Three trees are rendered in woodcuts by Schoeffer. Why was Savin considered so important that Savin ointment is still sold by homeopathic pharmacists?

Why were trees and/or illustrations purged from herbals when Dioscorides refers to cherry, cinnamon, elm, lemon, nutmeg, palm, pear, and pine—yet modern medical plant lists include many of them? Does it reveal the cultural importance of Savin which has been variously, and with some contradiction, accessed to treat both female and male maladies including excess bleeding, abortion, and syphilitic warts?

Roman “Anastasis” with trees sarcophagus. 340-350 CE, marble.

While very few trees are illustrated in De Materia Medica, and virtually none in Western herbals, we know that during antiquity trees were highly valued for more than their medicinal value. Detailed financial records relate to deforestation for building, funeral pyres, and to maintain naval prowess. In addition to the importance of trees for victory at sea, they were necessary for home construction, kiln upkeep, and foodstuffs. They were valued, accurately observed, and planted simply for their beauty. It has been said that the wealthy, in the tradition of 6th century BCE Nebuchadnezzar, created tree gardens just for shade, flowers, fragrance, and remembrance. Before the plethora of 14th century herbals with which botanical artists are familiar, there were artistic renderings of trees surviving in media other than a traditional watercolor or ink wash. So while I began this quest for the art of the tree in Mediterranean botanical art,

Gold myrtle, Greek

I paused to consider that the Egyptians represented identifiable date palms, fruit trees, and sycamores on polychrome frescoes (Nebamum Estate 1350 BCE), the Greeks crowned their heroes with golden laurel (Hellenistic period 323-31 BCE), the Romans chiseled Anastasis sarcophagi with trees (340-350 CE), and carved diptychs of ritual practice under oak trees (Symmachi 388-401 CE) centuries prior to the botanical illustrations on parchment with which we are more familiar. In my years of study, I have not located images of trees so important to the work of architects and shipbuilders, only charts of their height and girth.

When trees were removed from herbals the tree became an allegory for human kinship, networks, and hierarchy, as well as a provider of political and spiritual messages. Does the tree need to be returned to the natural and botanical world?

Salix, willow, Herbarius Latinus